Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a primary lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that is currently regarded as a variant of lichen planopilaris. FFA has historically been considered rare in black patients, in whom traction alopecia, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and androgenetic alopecia are frequently assumed to be more common. JDD author Kimberly Huerth, MD, ME describes a case of FFA in a black woman that both clinically resembled androgenetic alopecia and lacked many of the physical exam and dermoscopic findings associated with FFA. In doing so, she highlights the need for physicians to have a high index of suspicion for FFA in any black patient who presents with frontotemporal alopecia.

REPORT OF A CASE

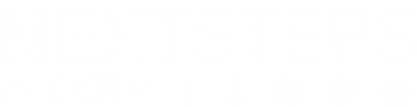

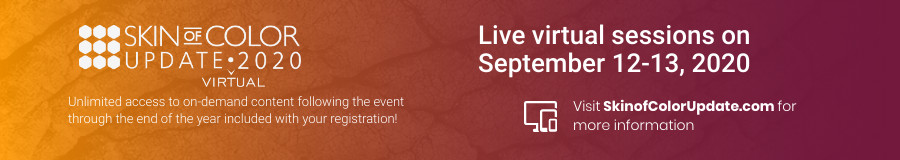

A 53-year-old African American woman presented with a 6-month history of asymptomatic, moderately severe hair loss along the frontal hairline, which had not stabilized or improved with minoxidil 2% solution BID. Physical exam revealed decreased hair density affecting the frontal scalp, suggestive of androgenetic alopecia (Figure1). Dermoscopic examination showed decreased follicular ostia without perifollicular scaling or erythema. Eyebrow alopecia, facial papules, and glabellar red dots were absent, and there was no associated loss of body hair. A 4-mm punch biopsy sent for histopathologic examination revealed dense, chronic, perifollicular inflammation affecting the mid and upper portions of the follicles, with loss of associated sebaceous glands. Involved hairs demonstrated vacuolar interface disruption of the basilar and epibasilar layers at the level of the isthmus and infundibulum, with prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes into the outer root sheath. There was no miniaturization, dermal mucin, or inflammation affecting the epidermis, arrector pili muscles, and eccrine glands (Figure 2).

A diagnosis of FFA was confirmed by these findings. Our patient was managed with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (10mg/cc) injections, clobetasol 0.05% ointment BID, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg PO BID, and minoxidil 5 mg PO daily. Unfortunately, her alopecia did not stabilize with these measures.

DISCUSSION

FFA is a primary lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that is currently regarded as a variant of lichen planopilaris. It is characterized by band-like frontotemporal hairline recession, often with associated eyebrow alopecia, perifollicular erythema, and scaling. Clinical findings are frequently accompanied by pruritus and burning of the affected scalp. Since it was first described in 1994,1 FFA has largely been viewed as an alopecia of post-menopausal Caucasian women. This archetype has been maintained by patient demographics of subsequent published case series.2,3 FFA may thus be underdiagnosed in black women, in whom traction alopecia, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and androgenetic alopecia are assumed to be more common. Furthermore, FFA can manifest uniquely in black women, who may be premenopausal4,5 and asymptomatic4 at the time of presentation. Classic signs of FFA may be subtle or absent among black patients, as increased pigmentation may render erythema difficult to appreciate, while oils and hair care products may diminish the appearance of scale.

It is important for dermatologists to both recognize that FFA is not uncommon in the black population,4,5 and to acknowledge how it initially came to be regarded as a disease of post-menopausal white women. Several of the larger published series come from geographic areas that lack a substantial skin of color population.2,3 There are also socioeconomic factors to consider. One series comprised exclusively of Caucasian women found their patients to be more affluent, which was speculated to be a surrogate marker for an unknown risk factor associated with the development of FFA.3 What these authors did not discuss, however, is that affluence enables access to specialty medical care. Affluence affects insurance status, which has been shown to vary widely among racial groups.6 Insurance status in turn bears upon who has access to dermatologic care, and who is ultimately included in a case series.

Although there are no universal treatment guidelines for FFA, the goal of management is to halt progression of the disease before follicles are irrevocably lost to fibrosis. Initiation of appropriate treatment requires a correct diagnosis, which is contingent upon a clinician’s willingness to consider certain conditions in patients who do not fit the paradigm that they have been taught. FFA must be considered in any black patient who presents with frontotemporal alopecia.

References

3. MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):955-961. doi: 10.1016/j. jaad.2011.12.038.

4. Callender VD, Reid SD, Obayan O, et al. Diagnostic clues to frontal fibrosing alopecia in patients of African descent. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(4):45-51.

5. Dlova NC, Jordaan HF, Skenjane A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A clinical review of 20 black patients from South Africa. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(4):939-41.

6. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Key facts on health and health care by race and ethnicity. http://www.kff.org/report-section/key-facts-on-healthand- health-careby-race-and-ethnicity-section-4-health-coverage/. Accessed December 8, 2018.

Source:

Kimberly Huerth MD ME (2020). Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Presenting as Androgenetic Alopecia in an African American Woman. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, 19 (7). https://jddonline.com/articles/dermatology/S1545961620P0202X

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this case report? Find more here.

Next Steps in Derm is brought to you by SanovaWorks.