Thalidomide was introduced in the 1950s as a “safe” sleeping medication; however, it quickly became vilified and was removed from the market for its severe teratogenic effects, most commonly phecomelia, or loss of arms and legs. Despite these devastating birth defects, thalidomide has a variety of indications for dermatologic conditions, with manageable side effects when used appropriately. We continue our series, Therapeutic Cheat Sheet, with a closer look at thalidomide, which is FDA-approved for erythema nodosum leprosum and multiple myeloma, and is also used off-label for a variety of inflammatory, autoimmune, and pruritic conditions.

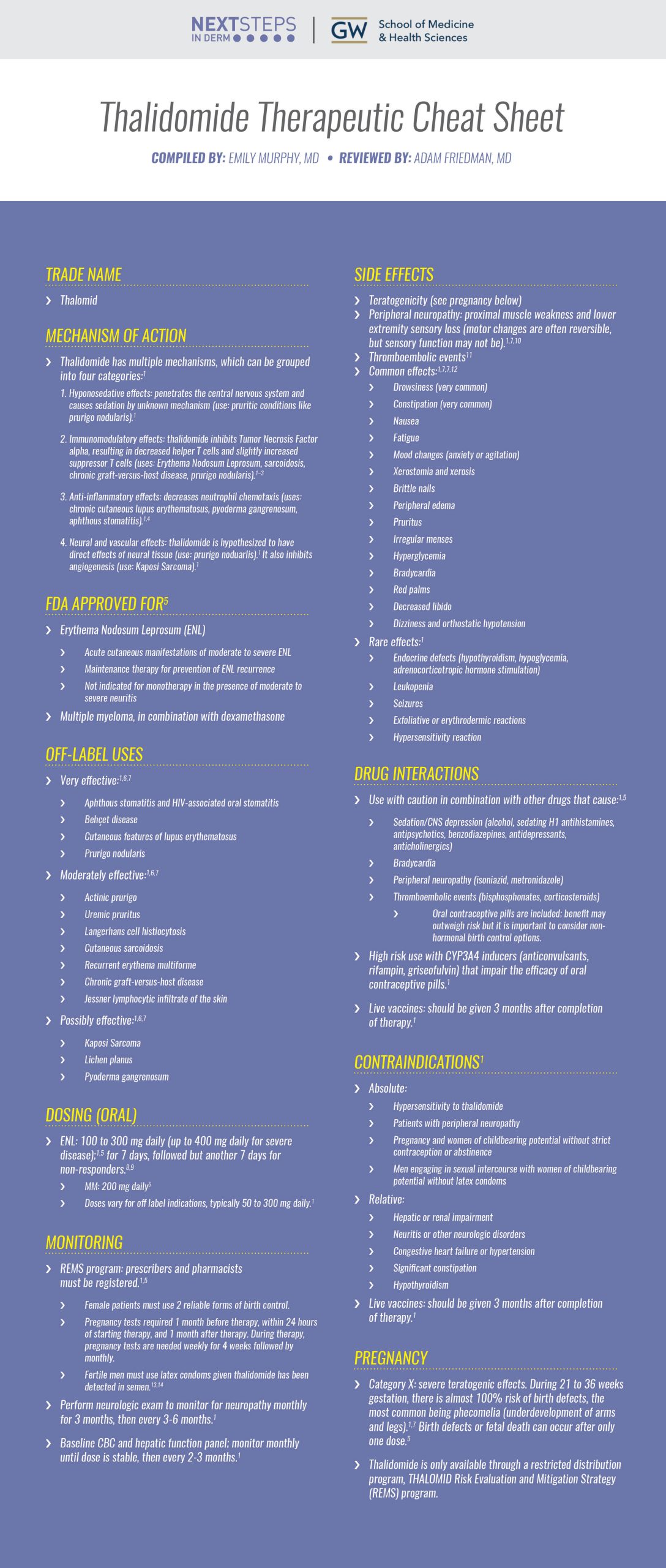

THALIDOMIDE THERAPEUTIC CHEAT SHEET

Compiled by: Emily Murphy, MD | Reviewed by: Adam Friedman, MD

THALIDOMIDE TRADE NAME

-

- Thalomid

MECHANISM OF ACTION OF THALIDOMIDE

-

- Thalidomide has multiple mechanisms, which can be grouped into four categories:1

- Hyponosedative effects: penetrates the central nervous system and causes sedation by unknown mechanism (use: pruritic conditions like prurigo nodularis).1

- Immunomodulatory effects: thalidomide inhibits Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha, resulting in decreased helper T cells and slightly increased suppressor T cells (uses: Erythema Nodosum Leprosum, sarcoidosis, chronic graft-versus-host disease, prurigo nodularis).1–3

- Anti-inflammatory effects: decreases neutrophil chemotaxis (uses: chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, pyoderma gangrenosum, aphthous stomatitis).1,4

- Neural and vascular effects: thalidomide is hypothesized to have direct effects of neural tissue (use: prurigo noduarlis).1 It also inhibits angiogenesis (use: Kaposi Sarcoma).1

WHAT IS THALIDOMIDE FDA APPROVED FOR?5

-

- Erythema Nodosum Leprosum (ENL)

- Acute cutaneous manifestations of moderate to severe ENL

- Maintenance therapy for prevention of ENL recurrence

- Not indicated for monotherapy in the presence of moderate to severe neuritis

- Multiple myeloma, in combination with dexamethasone

- Erythema Nodosum Leprosum (ENL)

OFF-LABEL USES OF THALIDOMIDE

-

- Very effective:1,6,7

- Aphthous stomatitis and HIV-associated oral stomatitis

- Behçet disease

- Cutaneous features of lupus erythematosus

- Prurigo nodularis

- Moderately effective:1,6,7

- Actinic prurigo

- Uremic pruritus

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis

- Recurrent erythema multiforme

- Chronic graft-versus-host disease

- Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin

- Possibly effective:1,6,7

- Kaposi Sarcoma

- Lichen planus

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

- Very effective:1,6,7

THALIDOMIDE DOSING (ORAL)

-

- ENL: 100 to 300 mg daily (up to 400 mg daily for severe disease);1,5 for 7 days, followed but another 7 days for non-responders.8,9

- MM: 200 mg daily5

- Doses vary for off label indications, typically 50 to 300 mg daily.1

THALIDOMIDE SIDE EFFECTS

-

- Teratogenicity (see pregnancy below)

- Peripheral neuropathy: proximal muscle weakness and lower extremity sensory loss (motor changes are often reversible, but sensory function may not be).1,7,10

- Thromboembolic events11

- Common effects:1,7,7,12

- Drowsiness (very common)

- Constipation (very common)

- Nausea

- Fatigue

- Mood changes (anxiety or agitation)

- Xerostomia and xerosis

- Brittle nails

- Peripheral edema

- Pruritus

- Irregular menses

- Hyperglycemia

- Bradycardia

- Red palms

- Decreased libido

- Dizziness and orthostatic hypotension

- Rare effects:1

- Endocrine defects (hypothyroidism, hypoglycemia, adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation)

- Leukopenia

- Seizures

- Exfoliative or erythrodermic reactions

- Hypersensitivity reaction

THALIDOMIDE DRUG INTERACTIONS

-

- Use with caution in combination with other drugs that cause:1,5

- Sedation/CNS depression (alcohol, sedating H1 antihistamines, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, anticholinergics)

- Bradycardia

- Peripheral neuropathy (isoniazid, metronidazole)

- Thromboembolic events (bisphosphonates, corticosteroids)

- Oral contraceptive pills are included; benefit may outweigh risk but it is important to consider non-hormonal birth control options.

- High risk use with CYP3A4 inducers (anticonvulsants, rifampin, griseofulvin) that impair the efficacy of oral contraceptive pills.1

- Live vaccines: should be given 3 months after completion of therapy.1

- Use with caution in combination with other drugs that cause:1,5

CONTRAINDICATIONS1

-

- Absolute:

- Hypersensitivity to thalidomide

- Patients with peripheral neuropathy

- Pregnancy and women of childbearing potential without strict contraception or abstinence

- Men engaging in sexual intercourse with women of childbearing potential without latex condoms

- Relative:

- Hepatic or renal impairment

- Neuritis or other neurologic disorders

- Congestive heart failure or hypertension

- Significant constipation

- Hypothyroidism

- Absolute:

PREGNANCY

-

- Category X: severe teratogenic effects. During 21 to 36 weeks gestation, there is almost 100% risk of birth defects, the most common being phecomelia (underdevelopment of arms and legs).1,7 Birth defects or fetal death can occur after only one dose.5

- Thalidomide is only available through a restricted distribution program, THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.

MONITORING

-

- REMS program: prescribers and pharmacists must be registered.1,5

- Female patients must use 2 reliable forms of birth control.

- Pregnancy tests required 1 month before therapy, within 24 hours of starting therapy, and 1 month after therapy. During therapy, pregnancy tests are needed weekly for 4 weeks followed by monthly.

- Fertile men must use latex condoms given thalidomide has been detected in semen.13,14

- Perform neurologic exam to monitor for neuropathy monthly for 3 months, then every 3-6 months.1

- Baseline CBC and hepatic function panel; monitor monthly until dose is stable, then every 2-3 months.1

- REMS program: prescribers and pharmacists must be registered.1,5

CLICK ON THE IMAGE BELOW TO ENLARGE AND/OR DOWNLOAD YOUR THERAPEUTIC CHEAT SHEET

FURTHER READING

If you would like to learn more about thalidomide, check out the following articles published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology:

Frank Martiniuk, Jerome Giovinazzo, Ainah U. Tan, Rozana Shahidullah, Patrick Haslett, Gilla Kaplan, and William R. Levis

Abstract:

Background: Leprosy was the first disease classified according to the thymus derived T-cell in the 1960s and the first disease classified by the cytokine profile as intact interferon-γ(IFN-γ) and interleukin-2 (IL2) or TH1 (tuberculoid) and deficient IFN-γ and IL2 or TH2 (lepromatous), in the 1980s.

Objective: In the present study, we set out to explore the T helper 17 (TH17) lymphocyte subset, the hallmark of T-cell plasticity, in skin biopsies from patients with erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) who were treated with thalidomide.

Method: RNA was extracted from paraffin embedded tissue before and after thalidomide treatment of ENL and RT-PCR was performed.

Results: IL17A, the hallmark of TH17, was consistently seen before and after thalidomide treatment, confirming the TH17 subset to be involved in ENL and potentially up-regulated by thalidomide.

Conclusion: A reduction in CD70, GARP, IDO, IL17B (IL-20), and IL17E (IL-25) , coupled with increases in RORγT, ARNT, FoxP3, and IL17C (IL-21) following thalidomide treatment, opens the door to understanding the complexity of the immunomodulatory drug thalidomide, which can operate as an anti-inflammatory while simultaneously stimulating cell-mediated immunity (CMI). We conclude that TH17 is involved in the immunopathogenesis of ENL and that thalidomide suppresses inflammatory components of TH17, while enhancing other components of TH17 that are potentially involved in CMI.

J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(5):626-630.

Sabrina Guillen Fabi, Carlotta Hill, Joslyn N. Witherspoon, Susan L. Boone, Dennis P. West

Abstract:

Thalidomide is increasingly being used due to its effectiveness in the treatment of a variety of dermatologic conditions refractory to other treatments. Although thalidomide’s side effects have been well-documented in the literature since its entry in the 1950s, some of the risks associated with its use are still being discovered. Recently, increased incidence of venous thrombosis following thalidomide use has been reported in the treatment of diseases with disease-related thrombotic risks, such as malignancy and lupus with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, as well as concomitant therapy with chemotherapy and/or systemic corticosteroids. We report a case of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus (PE) following thalidomide use in a patient with leprosy (erythema nodosum leprosum, ENL) who was concurrently treated with prednisone, as well as a review of relevant literature. Our findings substantiate an increase in risk for thrombosis following thalidomide use in the dermatology and non-cancer clinical setting.

J Drugs Dermatol. 2009; 8(8):765.

A Case-series of 48 Patients Treated WithThalidomide

Sean D. Doherty, Sylvia Hsu

Abstract:

Introduction: Thalidomide is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for erythema nodosum leprosum, but has been used in many other dermatological conditions that are refractory to standard therapy.

Methods: The medical records of 48 patients treated with thalidomide at Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX) were retrospectively reviewed to determine the conditions treated with thalidomide, dosing, effi cacy, treatment duration, side effects, adverse events, and reason for discontinuing therapy.

Results: Forty-eight patients (men=18, women=30) with a mean age of 49.6 years (range: 20-79) were included in this study. Patients were treated for prurigo nodularis, discoid lupus erythematosus, tumid lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, systemic lupus erythematosus, lichen planus, lichen planopilaris, cutaneous sarcoidosis, and prurigo nodularis. All conditions were refractory to standard therapy. Patients were treated for a mean of 7.5 months (range: 3 days to 70 months). In most of the disorders, a majority of patients experienced clinical improvement. The most common reason for discontinuation of therapy was side effects, the most frequent being peripheral neuropathy.

Limitations: This study was limited by being retrospective in nature.

Conclusion: Thalidomide effectively treats some dermatologic conditions that are refractory to standard medications. There are inconveniences associated with obtaining the medication and it is expensive. Physicians must be vigilant for possible side effects, especially peripheral neuropathy.

J Drugs Dermatol. 2008; 7(8):769.

References

-

- Davis L, Owen C. Miscellaneous Systemic Drugs, Chapter 40. In: Wolverton S, Wu J, eds. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. Fourth Edition. Elsevier; :445-464.e6. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www-clinicalkey-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/#!/content/book/3-s2.0-B9780323612111000401?indexOverride=GLOBAL

- Sampaio EP, Sarno EN, Galilly R, Cohn ZA, Kaplan G. Thalidomide selectively inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha production by stimulated human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173(3):699-703. doi:10.1084/jem.173.3.699

- Gad SM, Shannon EJ, Krotoski WA, Hastings RC. Thalidomide induces imbalances in T-lymphocyte sub-populations in the circulating blood of healthy males. Lepr Rev. 1985;56(1):35-39. doi:10.5935/0305-7518.19850006

- Faure M, Thivolet J, Gaucherand M. Inhibition of PMN leukocytes chemotaxis by thalidomide. Arch Dermatol Res. 1980;269(3):275-280. doi:10.1007/BF00406421

- Bristol Myers Squibb. Thalidomide. Package Insert. Published online October 2019.

- Wu JJ, Huang DB, Pang KR, Hsu S, Tyring SK. Thalidomide: dermatological indications, mechanisms of action and side-effects. British Journal of Dermatology. 2005;153(2):254-273. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06747.x

- Tseng S, Pak G, Washenik K, Pomeranz MK, Shupack JL. Rediscovering thalidomide: a review of its mechanism of action, side effects, and potential uses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(6):969-979. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90122-x

- Iyer CG, Languillon J, Ramanujam K, et al. WHO co-ordinated short-term double-blind trial with thalidomide in the treatment of acute lepra reactions in male lepromatous patients. Bull World Health Organ. 1971;45(6):719-732.

- Sheskin J, Convit J. Results of a double blind study of the influence of thalidomide on the lepra reaction. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1969;37(2):135-146.

- Moraes M, Russo G. Thalidomide and its dermatologic uses. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321(5):321-326. doi:10.1097/00000441-200105000-00004

- Cesbron E, Bessis D, Jachiet M, et al. Risk of thromboembolic events in patients treated with thalidomide for cutaneous lupus erythematosus: A multicenter retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(1):162-165. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.049

- Clemmensen OJ, Olsen PZ, Andersen KE. Thalidomide neurotoxicity. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120(3):338-341.

- Ochonisky S, Verroust J, Bastuji-Garin S, Gherardi R, Revuz J. Thalidomide neuropathy incidence and clinico-electrophysiologic findings in 42 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(1):66-69.

- Briani C, Zara G, Rondinone R, et al. Thalidomide neurotoxicity: prospective study in patients with lupus erythematosus. Neurology. 2004;62(12):2288-2290. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000130499.91775.2c

Did you enjoy this therapeutic cheat sheet? You can find more here.