Hair Apparent: A Multi-Part Series on Hair Disorders – Part II

If you missed Part I, click here.

Dermatology residents from throughout the Washington DC area recently convened at the Georgetown University MedStar Washington Hospital Center Hair Disorders Symposium, where distinguished experts in the field of hair disorders discussed the evaluation, work-up, and treatment of a wide variety of alopecias and scalp disorders. A treasure trove of clinical pearls was shared along the way, and the attendees learned a host of new strategies to apply to the management of hair loss, which is both widely prevalent and frequently undertreated.

This post is the second of a multi-part series that summarizes salient points from each of the lectures, as well as strategies that residents can add to their alopecia armamentarium.

Today’s post will be devoted to Dr. Valerie Callender’s lecture on the evaluation and medical management of scarring alopecias (namely central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia and frontal fibrosing alopecia), with a particular focus on how to tailor treatment to meet the needs of black women. Dr. Callender is a professor of dermatology at Howard University, the founder of the Callender Dermatology and Cosmetic Center located in Glenn Dale, MD, and is on the board of directors of the American Academy of Dermatology. She is an expert in alopecia as well as pigmentary disorders, particularly in skin of color. The following aspects of her lecture will be shared in this post:

- Unique clinical presentation in black women

- Diagnosis

- Treatment: Active phase and maintenance

- Collaboration with the hair salon

- Clinical pearls!

Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia (CCCA)

CCCA is the most prevalent form of scarring alopecia among patients of African descent, with women more commonly affected than men. While the exact pathogenesis of CCCA is unknown, hairstyling practices that place tension on the hair shaft and caustic hair care products may possibly exacerbate the disease and its progression. What is known, however, is that failure to diagnose and appropriately treat this disorder early can lead to permanent inflammatory-mediated destruction of the pilosebaceous unit, potentially manifesting as a large swath of alopecia on the crown and/or vertex scalp.

Presentation

Patients will often present with scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pruritus, burning, and tingling, though some are asymptomatic. Hair breakage may also be a presenting sign of early or occult CCCA, especially if this is occurring in the setting of the aforementioned scalp symptoms. When these symptoms occur in women with a known history of uterine leiomyomas, a higher index of suspicion for CCCA is warranted, given the association that exists between these fibroproliferative disorders.

CCCA classically, though not exclusively, presents on the central vertex scalp, and spreads symmetrically outward in a centrifugal fashion while the disease is active. It is also possible for other forms of alopecia, such as female pattern hair loss and traction alopecia, to exist concomitantly with CCCA. When this is the case, diagnosis based on gross visual examination alone can be challenging. Comorbid seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp is a common finding in CCCA patients, and is attributable to a myriad of factors that limit the frequency of hair washing to no more than once every one to two weeks for a number of women with textured hair.

Diagnosis

As can be seen, there are several non-specific findings that may be suggestive of CCCA before the disease has fully declared itself. Dermoscopy is a tool that can be used to identify active disease before it has progressed to irreversible end-stage fibrosis. Dermoscopic findings that support a diagnosis of CCCA include:

- Peripilar white/gray halo around emerging hairs (representing the outer root sheath with surrounding perifollicular fibrosis)

- Peripilar erythema

- White patches of follicular scarring interrupting a honeycomb pigmented network

- Numerous irregularly distributed, interfollicular pinpoint white dots (follicular and acrosyringial openings)

- Broken hairs/black dots

- Hair shaft variability

- Scaling

If the diagnosis remains in doubt despite a careful dermoscopic examination, tissue for histopathologic examination should be obtained. Biopsy is both extremely valuable and frequently underutilized in patients who are reporting scalp symptoms in the absence of classic CCCA findings. Two punch biopsies, for horizontal and vertical sectioning, should be obtained from the active border of the hair loss, or from the symptomatic area if alopecia is not yet apparent.

Treatment

Treatment of CCCA should initially be targeted at halting the progression of active disease, followed by maintenance of remission once symptoms have improved. A multifaceted approach is required to quell active CCCA. Although there are no universally accepted treatment guidelines, a regimen that is guided by the following may yield good results.

Active Phase:

- Doxycycline 100 mg PO BID for 8 – 12 weeks

- High potency topical steroid to the affected area three times per week

- Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 5 mg/cc every 4 – 6 weeks for a total of 3 – 4 rounds of injections. Injections should target both the alopecic area and its periphery.

- Anti-seborrheic shampoo (ciclopirox, ketoconazole, pyrithione zinc) once every 1 – 2 weeks (depending on the hair washing schedule of the patient)

Maintenance Phase:

- Transition from a high to mid potency topical steroid three times per week

- Continue the anti-seborrheic shampoo

- Continue to utilize intralesional steroid injections on an as needed basis for foci where, based on reported patient symptoms, the disease may be more active

- Add topical minoxidil 5% solution or foam daily to BID as tolerated by the patient (use may be limited by side effects such as hypertrichosis, or scalp pruritus due to the drying effect of the vehicle)

The Hair Salon as an Ally In Treating the Disease

Addressing comorbid seborrheic dermatitis is an important part of the treatment regimen for CCCA. Many patients with textured and un-textured hair alike, however, complain that shampoos employed for this purpose (ketoconazole, salicylic acid, coal-tar) are drying, and therefore predispose hair to increased breakage. Those who have their hair washed at a salon every one to two weeks should be advised to bring their anti-seborrheic shampoo with them for use at their appointments; those who are washing their hair less frequently should be gently encouraged do to so more often. Patients should instruct the salon employee washing their hair to apply the shampoo directly to the scalp, and to leave it in place for several minutes before rinsing. Once the anti-seborrheic shampoo has been rinsed out, additional use of moisturizing shampoos and conditioners for the hair itself, as well as post-wash moisturizing treatments to combat drying and breakage, are permissible.

Although the ultimate role that tension promoting hairstyles and chemical relaxers have in the pathogenesis and progression of CCCA continues to be debated, both practices are capable of promoting hair loss and breakage via other mechanisms. If a woman wishes to continue chemical relaxers, the dermatologist can recommend that she request a milder relaxer or a sensitive scalp formulation, and that either she or the stylist base the entire scalp (apply petroleum jelly or equivalent) prior to relaxer application. Other strategies that may assist patients with minimizing their exposure to caustic salon chemicals include decreasing the frequency of relaxer touch ups, or taking periodic relaxer holidays (when the hair can be styled in loose braids or a wig can be worn). Amenable patients should be gently encouraged to work with their hair stylists to gradually transition to natural hairstyles when possible, with coiffing geared towards camouflaging areas where follicles have been permanently replaced with fibrosis.

Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia (FFA)

FFA is a cicatricial hair loss that is currently regarded as a variant of lichen planopilaris (LPP), and is characterized by frontal and temporoparietal recession of the hairline. The disease may be indolent or rapid in its progression, though most cases do eventually spontaneously remit. The etiology of FFA is unknown, and there are no universal treatment guidelines. The archetypal FFA patient is a post-menopausal Caucasian woman, and for this reason, FFA may be underdiagnosed, particularly in black women, who may be more commonly assumed to exhibit other forms of scarring hair loss such as CCCA and traction alopecia. It is of import to note that black women with FFA often experience fewer symptoms and unique clinical presentations. Because many physicians may not be aware of this, accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment initiation may be delayed, much to the detriment of the patient.

Presentation

FFA classically affects the frontal and temporoparietal scalp, though the occipital scalp may also be involved. Perifollicular erythema and scaling, with associated pruritus and tenderness is often, but not always present. The “lonely hair sign,” which refers to the presence of one or a few isolated terminal hairs in the middle of the forehead, surrounded by skin that has lost all follicular ostia, can also be a useful diagnostic clue. FFA can additionally present with alopecia of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair, as well as non-inflammatory facial papules and glabellar red dots. The latter two findings are indicative of facial vellus hair involvement.

FFA may present uniquely in black patients. For example, unlike their white counterparts, black women with FFA may be more likely be premenopausal at the time of presentation. Scalp erythema, generally considered a hallmark of the disease, may be muted or obscured by background pigmentation, or even wholly absent. Post-inflammatory changes can also lead to unique findings, such as follicular hyperpigmentation that imparts a speckled appearance of the frontal hairline. Alternatively, post-inflammatory hypopigmentation may be observed along the frontal hairline.

Diagnosis

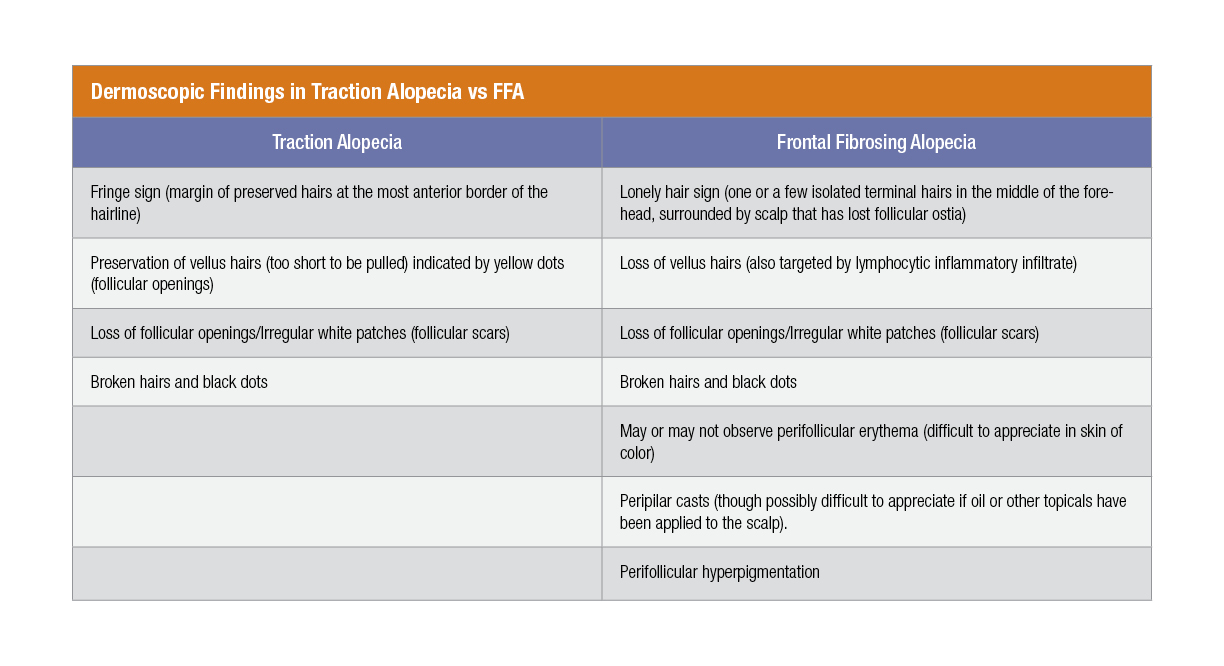

As is the case with CCCA, symptoms suggestive of inflammation (burning, tingling, pruritus, pain) may precede appreciable alopecia, and should not be reflexively attributed to seborrheic dermatitis or hair styling practices. Though the differential diagnosis of marginal hair loss in black women also includes such common entities as androgenetic alopecia, alopecia areata, and traction alopecia, FFA should also be considered, especially given that it may be underdiagnosed in this population. Demoscopy can be an extremely helpful tool when trying to differentiate between FFA and traction alopecia, given that the distribution of hair loss in both conditions appears grossly similar, and that most women will attest to having styled their hair in a tension promoting manner at some point during their lives.

Dermoscopic Findings in Traction Alopecia vs FFA

Click image to enlarge In the absence of classic clinical or dermoscopic findings, or if concomitant traction and/or androgenetic alopecia are muddying the waters, punch biopsies (as discussed in the CCCA section) should be obtained for histopathologic examination.

In the absence of classic clinical or dermoscopic findings, or if concomitant traction and/or androgenetic alopecia are muddying the waters, punch biopsies (as discussed in the CCCA section) should be obtained for histopathologic examination.

Treatment

There is unfortunately no standardized treatment protocol for FFA. Therapy selected is contingent upon the patient’s willingness to proceed with topical vs systemic medications, the physician’s comfort level and success rate with certain therapies, and the extent to which a patient appears to be responding to treatment. Treatments that have been tried with varying degrees of success include:

- Topical, intralesional, or systemic corticosteroids

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors

- Tetracyclines (doxycycline)

- Antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine)

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (finasteride, dutasteride)

- Systemic retinoids (isotretinoin, acitretin)

- Steroid sparing immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclosporine)

- PPAR-agonists (pioglitazone)

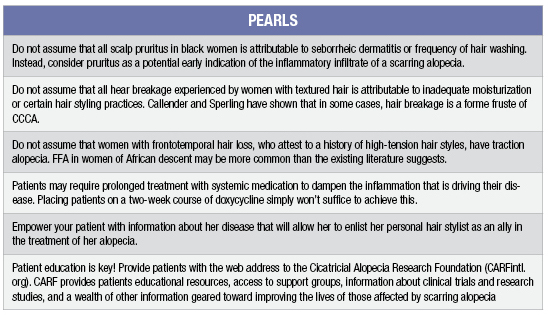

Pearls

If you missed part 1 of this series, check it out here.