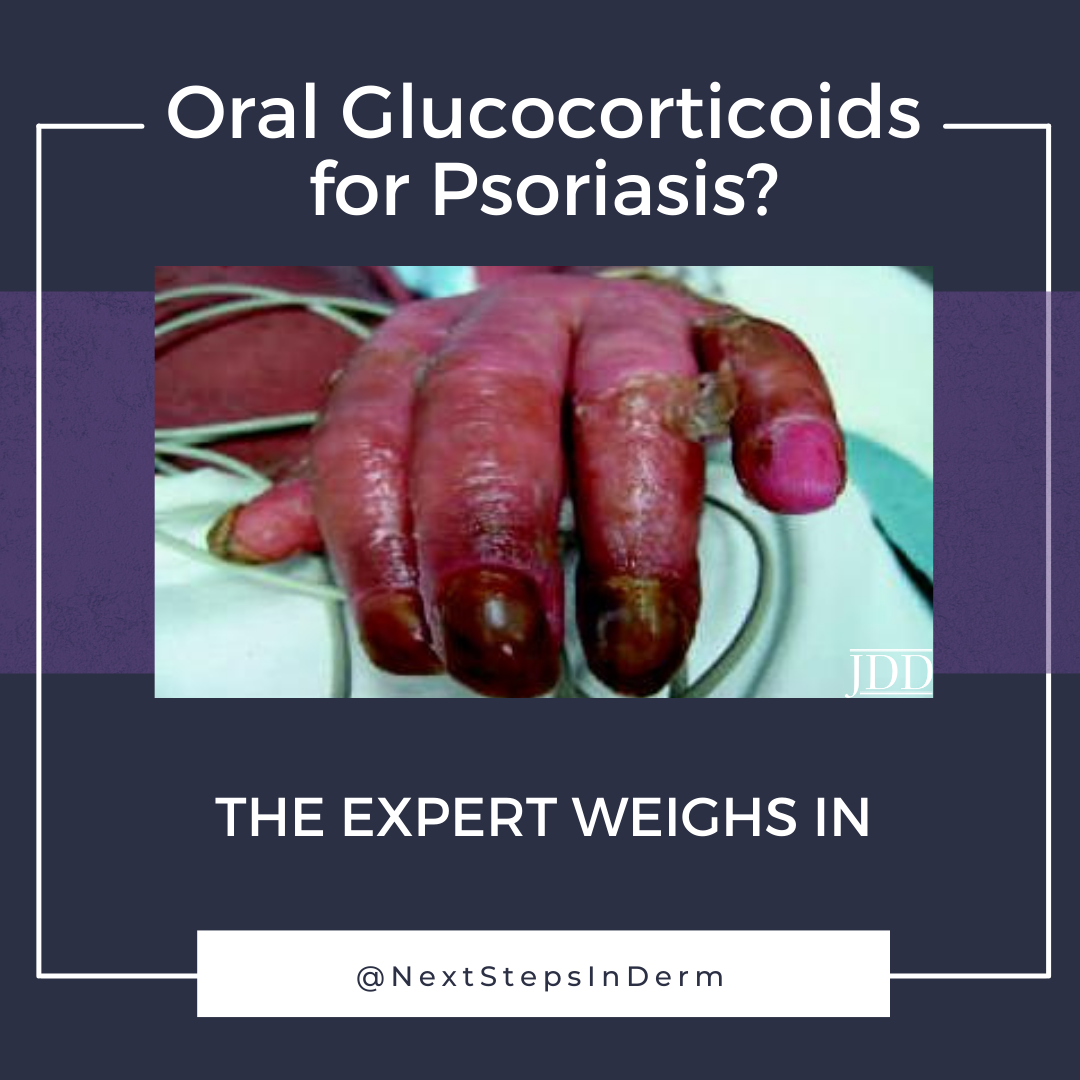

Dermatologists are prescribing oral glucocorticoids for psoriasis despite awareness of risks of life-threatening generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) and erythrodermic psoriasis (EP). A recent survey of dermatologists published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology found 18% of respondents occasionally prescribe oral glucocorticoids to patients with psoriasis, typically 1-5% of the time. Those who prescribe oral glucocorticoids tended to be younger with two-thirds in clinical practice for ten years or less.

So why are some dermatologists occasionally prescribing oral glucocorticoids for psoriasis, and is the usage worth urgency in examining the relationship between oral glucocorticoid use and development of GPP and EP, as the authors note?

I interviewed George Han, MD, PhD, director of clinical dermatology and teledermatology, and associate professor of dermatology at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell. Dr. Han will be presenting on psoriasis at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference.

This study found 18% of responding U.S. dermatologists occasionally prescribed oral glucocorticoids despite a near universal knowledge of risks. Why do you think this was the case?

There are situations where oral corticosteroid use is reasonable, and the paper itself pointed out that oftentimes the steroids were used as a bridge to other systemic therapy. Ironically, the most appropriate use of oral steroids would probably be to get a severe case of pustular psoriasis under control while bridging to another therapy, which historically has been biologics, such as infliximab. However, targeted therapies for pustular psoriasis are on the horizon so this use case is likely less relevant. I would take this study with a grain of salt, as it only surveyed 50 dermatologists. That being said, an earlier study that was also published by Dr. Feldman’s group looked at a much larger database, finding that 650,000 of 21,000,000 psoriasis visits (approximately 3%) between 1989-2010 involved prescribing a systemic corticosteroid, with 93% of these visits being conducted by dermatologists. Clearly, whether or not the idea that corticosteroids are risky for triggering pustular psoriasis is true, a significant number of patients with psoriasis are still getting prescribed systemic corticosteroids in dermatologists’ offices.

The study found prescribers tended to be younger and most often in clinical practice for 10 years or less. Do you have any thoughts as to why?

I think that we, as dermatologists, are often like the proverbial elephant. We have excellent memories, especially for striking or negative experiences. For a long time, I shied away from prescribing oral minocycline because of a few severe cases of DRESS that I saw during residency. Due to the fact that psoriasis flares with systemic steroid administration are relatively rare events (1.42% among a recent cohort), prescribers may not have a high likelihood of seeing a negative outcome with the first few cases of psoriasis where they dabble with some steroids. This becomes a self-reinforcing trend, where each time you step a bit closer to the edge of the cliff, daring oneself to fall off. Once you see a patient with a severe psoriasis flare that seemed to be triggered by a steroid taper, though, it’s hard to forget it. Younger derms who have not seen a case of GPP/EP triggered by steroids, and who have been following the literature of the past decade or so seeming to debunk this so-called myth, are thus more likely to try using it when the situation seems reasonable – perhaps to help someone quickly clear while getting approval for a biologic. In this regard, prednisone tapers are much easier to start than cyclosporine, logistically, so that may have something to do with this trend as well.

Sixteen percent of respondents reported seeing at least one case of GPP/EP related to oral glucocorticoids. What are your thoughts on the risk/benefit profile of oral glucocorticoids in psoriasis?

In the modern age of biologics, it’s hard to imagine situations where steroids are truly necessary. If speed is the issue, some of our biologics can lead to rapid clearance within a week or two, such as brodalumab, ixekizumab, and potentially, bimekizumab. We will soon have targeted therapies for generalized pustular psoriasis which work, likewise, within a week or two. Finally, there may be some situations where, for treating psoriatic arthritis, one may want to add oral glucocorticoids to a treatment regimen encompassing DMARD’s/biologics, but this seems to be more the realm of the rheumatologist than within the wheelhouse of dermatology.

In my opinion, even if we accept that the risk is quite small (under 2%) for triggering a pustular psoriasis flare with systemic steroids, the biologics we have for psoriasis don’t have that risk and are much safer than systemic steroids as well. There is no component of a risk/benefit profile that would strongly support use of oral glucocorticoids in a dermatology practice for treating psoriasis.

In your expertise, are there any situations that warrant considering oral glucocorticoids as a treatment option, such as bridging to biologic therapy?

I think the most compelling current reason for treating psoriasis with a systemic steroid is the inpatient who is flaring with pustular psoriasis and developing systemic signs essentially mimicking sepsis where we need to rapidly reduce systemic inflammation and buy some time for other treatments to take hold. In this situation, I may consider starting systemic steroids while getting labs and approval for infliximab and/or acitretin, depending on the situation. As above, the other main argument for low-dose oral steroids would be for additional joint coverage, but I don’t think this would be reasonable as monotherapy, and the risks of flaring pustular psoriasis are likely greatly mitigated by the background therapy that the patient would already be on. I do want to underscore, though, that I have seen amazing results with some of the faster IL-17 inhibitors, where I truly doubt that systemic steroids could possibly do any better. In this context, why mess with “dirty” systemic steroids when we have much cleaner targeted therapies?

The study authors see an urgency in examining the relationship between oral glucocorticoid use and development of GPP/EP given the frequency of prescribing. Do you agree?

It’s hard to contextualize this data given the lack of nuance that such a study could provide. The overall population of dermatologists (98% in the study) do recognize this risk and I hope are practicing “safe steroid use,” i.e. low doses, limited time of administration, and providing adjunctive therapy so the rug is not taken out from under the patient. From a scientific standpoint, though, I do think that it is about time we have a better understanding of this phenomenon. This will help us identify patients that are definite no-no’s for receiving systemic steroids, so that we can better prevent the potentially devastating outcome of GPP/EP. In doing so, we could gain additional clarity into triggers and pathogenic features of GPP/EP also. The fundamental challenge remains, though – how do we characterize and study a clinical entity that is both rare and transient?

How should dermatologists interpret this article in light of the larger context of available psoriasis treatments?

This study serves as a reminder that we still don’t have a good answer to the question, “what brings about psoriasis?” Whether it’s pustular, erythrodermic, guttate, or plaque psoriasis, it’s hard to find the exact point where a genetically susceptible patient is presented with the environmental trigger that sets their psoriasis off, often for the rest of their lives. In the case of GPP/EP, the stakes are higher, and we need a better understanding of triggers outside of the typical steroid withdrawal and BLAM (beta blockers, lithium, anti-malarials) dogma. In evaluating a study that has fundamentally conflicting findings (almost all dermatologists are aware of risks of GPP/EP flares with steroids, many have seen this in real practice, but a significant number still prescribe steroids in this context), it speaks to the fact that we need better research, data and education to make a compelling argument for or against the safety of a treatment regimen. While I find that modern-day medications are far superior to oral steroids in almost any capacity, it would be helpful for us to have a better understanding of the role of steroids in psoriasis so we can approach this topic with more knowledge.

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on Medical Dermatology here.