Psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory skin condition, affects about 2% of children. A small subset have isolated nail involvement refractory to topical treatment that can be disabling. The development of targeted biologic agents offers safe, effective options for children with moderate-to-severe skin and nail disease. A few are now Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for children.

INTRODUCTION

A previously healthy 3-year-old boy presented to our Pediatric Dermatology clinic with a 3-month history of marked nail dystrophy involving several fingers and toes. The differential diagnosis included onychomycosis and nail psoriasis. An initial trial of empiric terbinafine was recommended, pending fungal culture of nail clippings. This resulted negative 1 month later.

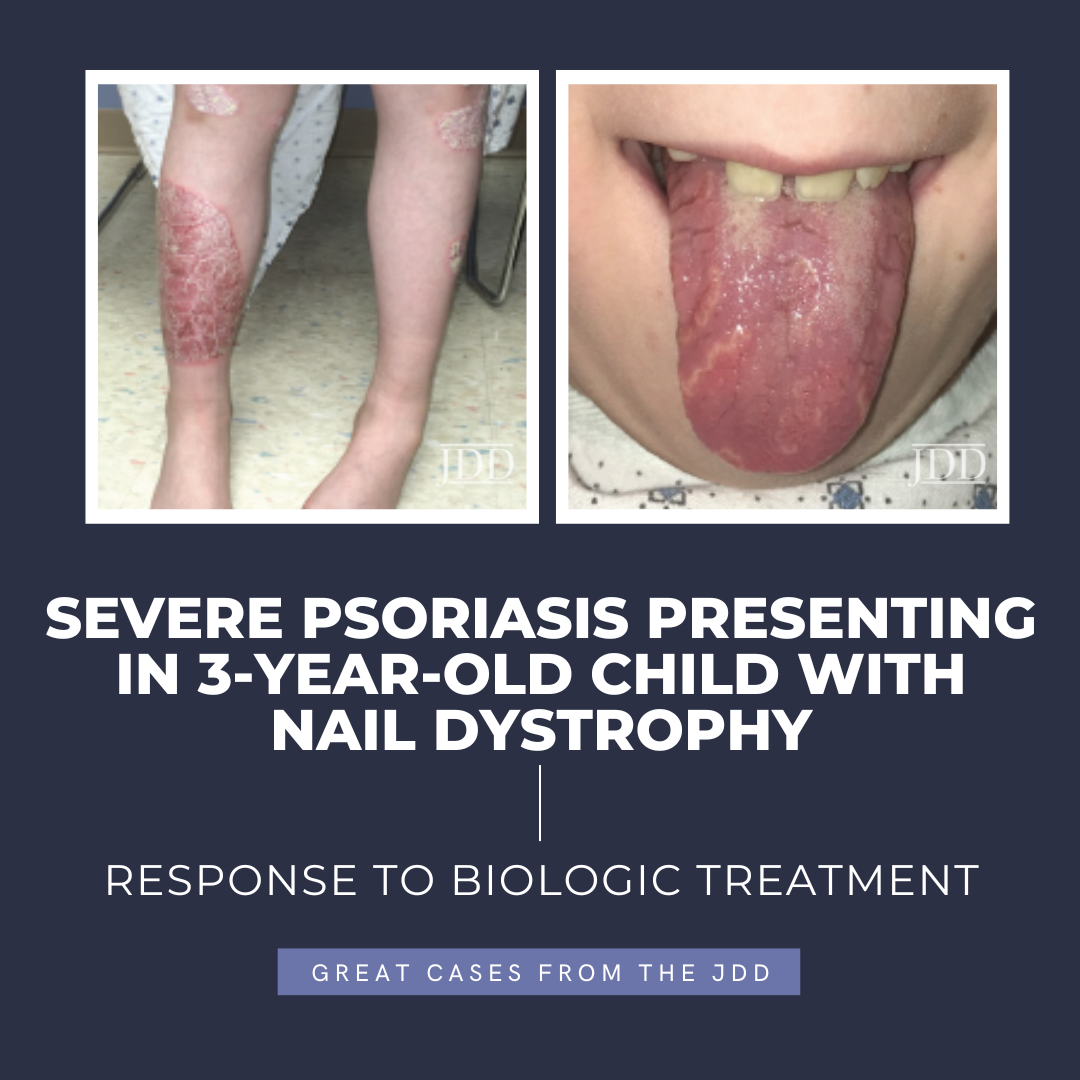

The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up for 5 years, returning for pruritic, psoriasiform skin lesions that had slowly spread over several years to involve his knees, arms, genitals, and scalp, with an estimated 10% body surface area (BSA). These findings, as well as geographic tongue and worsening nail dystrophy with associated paronychia, were characteristic of plaque psoriasis (see Figure 1).

Initial treatment with topical therapy was prescribed, as allowed by his insurance formulary, with alternating betamethasone and calcipotriene ointments, and ketoconazole shampoo as scalp and body wash. A 2-week trial of this regimen yielded minimal improvement.

The severity and extent of his psoriasis, including areas that were difficult-to-treat topically, met inclusion criteria for participation in a clinical trial of ixekizumab (Taltz®, Lilly), a biologic medication targeting IL-17, which was previously Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for psoriasis in adults. His scalp completely cleared within 1 week of the first injection. His nails and palms continued to improve with subsequent monthly injections, achieving 1% BSA (groin-only) involvement within 6 months. Complete clearing was achieved within 16 months, and maintain in the clinical trial on monthly ixekizumab injections.

The patient’s psoriasis reoccurred at age 11, 6 months off ixekizumab, and gradually worsened (See Figure 2.) During that time ixekizumab received FDA-approval for pediatric use but the patient’s insurance denied access to this treatment, with stepedits that required a failed trial of methotrexate. Weekly oral methotrexate was started 1 month later at 15 mg (0.3 mg/kg). His skin worsened over the next 2 months, and he complained of lower back and finger pain, prompting methotrexate increase to 20 mg (0.4 mg/kg) per week for 2 more months without significant benefit. Monthly laboratory monitoring was unremarkable. Ixekizumab was again prescribed and denied, based on additional insurance criteria requiring a trial of adalimumab (Humira®, Abbvie), despite lack of FDA-approval for this indication in children. The patient’s psoriasis improved to 5% BSA after 5 months of bimonthly adalimumab injections. A third attempt at access to ixekizumab was denied by his insurance.

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that affects more than 7 million Americans. Although this condition most often presents in young adults (peak onset 15-35 years old), 30% of cases begin in childhood, sometimes misdiagnosed as “nummular” eczema, or tinea.1,2,3 Plaque psoriasis is the most common phenotype in both children and adults,4 with acuteonset small “guttate” plaques classically developing after an infection such as strep throat, tonsillitis, or a respiratory infection.3 Other variants include nail, scalp, inverse, palmoplantar, and pustular psoriasis. In infants, psoriasis classically involves the face, diaper area, and scalp (often referred to as “cradle cap”).3,4 Geographic tongue is an associated, but underrecognized, often incidental finding.5 In children, nail and scalp involvement are often assumed to be fungal infections.6,7 Skin lesions triggered by physical trauma, a phenomenon known as “koebnerization,” is a characteristic feature of psoriasis.3,4 Grooming-associated koebnerization is believed to contribute to the increased incidence of scalp involvement in girls.4 Nail involvement may be subtle, manifesting as fine pits that can support the diagnosis, and has been associated with a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis.6 However, in severe cases, subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, discoloration, and paronychia can be disfiguring and painful, and interfere with function. The Child-CAPTURE registry identified nail involvement in psoriasis as a predictor of more severe disease.7,8

The pathogenesis of psoriasis involves immune dysregulation that has historically responded to treatment with broad systemic immunosuppressant medications (eg, cyclosporine and methotrexate). In the past 20 years, targeted biologic blockade of inflammatory cytokines has yielded increasingly better efficacy with fewer adverse effects. Biologic agents developed for the treatment of psoriasis include those that target TNFα, IL12/23, IL23, and IL17.9 These agents were initially studied and FDA-approved for treating psoriasis in adults. Additional pediatric trials and access to the evolving pipeline of medications was restricted for a minimum of 7 years after initial approval for each product. As of 2021, 4 biologic agents have been approved for pediatric use (Table 1.)9,11,12,13

Indications for systemic treatment include >10% BSA and sites that are difficult to treat topically (nails, groin, scalp) as well as failure to respond to standard-of-care topical therapy. Lowdose methotrexate used off-label is still considered a first-line systemic option and may be more well-tolerated in children than in adults. However, long-term treatment with methotrexate requires monitoring with baseline and frequent follow-up blood tests. Emerging level 1 data support safe and effective use of selected biologic agents in children without routine labs.9 Pediatric psoriasis can be a therapeutic challenge. Several parameters must be considered when electing the optimal treatment for a specific patient. These include primary morphology, speed of progression, age, gender, associated morbidities, medication cost, and access. In the absence of FDAapproved pediatric labelling, age has been the most common reason for insurance coverage denial for using biologic medications in children with psoriasis, which is an illegal form of age discrimination.14 Pediatric labelling has improved access for some treatments, but remains a challenge.

REFERENCES

2. Silverberg NB. Pediatric psoriasis: an update. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5:849-856. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s4908

3. Bronckers IMGJ, Paller AS, van Geel MJ, et al. Psoriasis in children and adolescents: diagnosis, management and comorbidities. Pediatr Drugs. 2015;17(5):373-384. doi:10.1007/s40272-015-0137-1

4. Mercy K, Kwasny M, Cordoro KM, et al. Clinical manifestations of pediatric psoriasis: results of a multicenter study in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(4):424-428. doi:10.1111/pde.12072

5. González-Ãlvarez L, GarcÃa-MartÃn JM, GarcÃa-Pola MJ. Association between geographic tongue and psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analyses. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019;48(5):365-372. doi:10.1111/jop.12840

6. Thomas L, Azad J, Takwale A. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46(1):3-8. doi:10.1111/ced.14314

7. Bronckers I, Bruins FM, van Geel MJ, et al. Nail involvement as a predictor of disease severity in paediatric psoriasis: follow-up data from the Dutch ChildCAPTURE registry. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(2):152-157. doi:10.2340/00015555-3036

8. Jiaravuthisan MM, Sasseville D, Vender RB, et al. Psoriasis of the nail: anatomy, pathology, clinical presentation, and a review of the literature on therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(1):1-27. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.073

9. Menter A, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):574]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):161-201. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.049

10. Bruins FM, Bronckers IMGJ, Groenewoud HMM, et al. Association between quality of life and improvement in psoriasis severity and extent in pediatric patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):72-78. doi:10.1001/ jamadermatol.2019.3717

11. Craig S, Warren RB. Ixekizumab for the treatment of psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;20(6):549-557. doi:10.1080/14712598.2020.172 9736

12. Kamata M, Tada Y. Efficacy and safety of biologics for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their impact on comorbidities: a literature review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1690. doi:10.3390/ijms21051690

13. Paller AS, Seyger MMB, Alejandro Magariños G, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in paediatric patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IXORAPEDS). Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(2):231-241. doi:10.1111/bjd.19147

14. Wang CY, Zheng RRC, Doerrer ZA, Kurta AO, Shelley JJ, Siegfried EC. Health care regulation, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and access to medicine: Our experience with dupilumab for children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):1568-1569. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.019

SOURCE

Rinck, D., & Siegfried, E. (2022). Severe Psoriasis Presenting in 3-Year-Old Child With Nail Dystrophy: Response to Biologic Treatment. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD, 21(8), 897-899.

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.