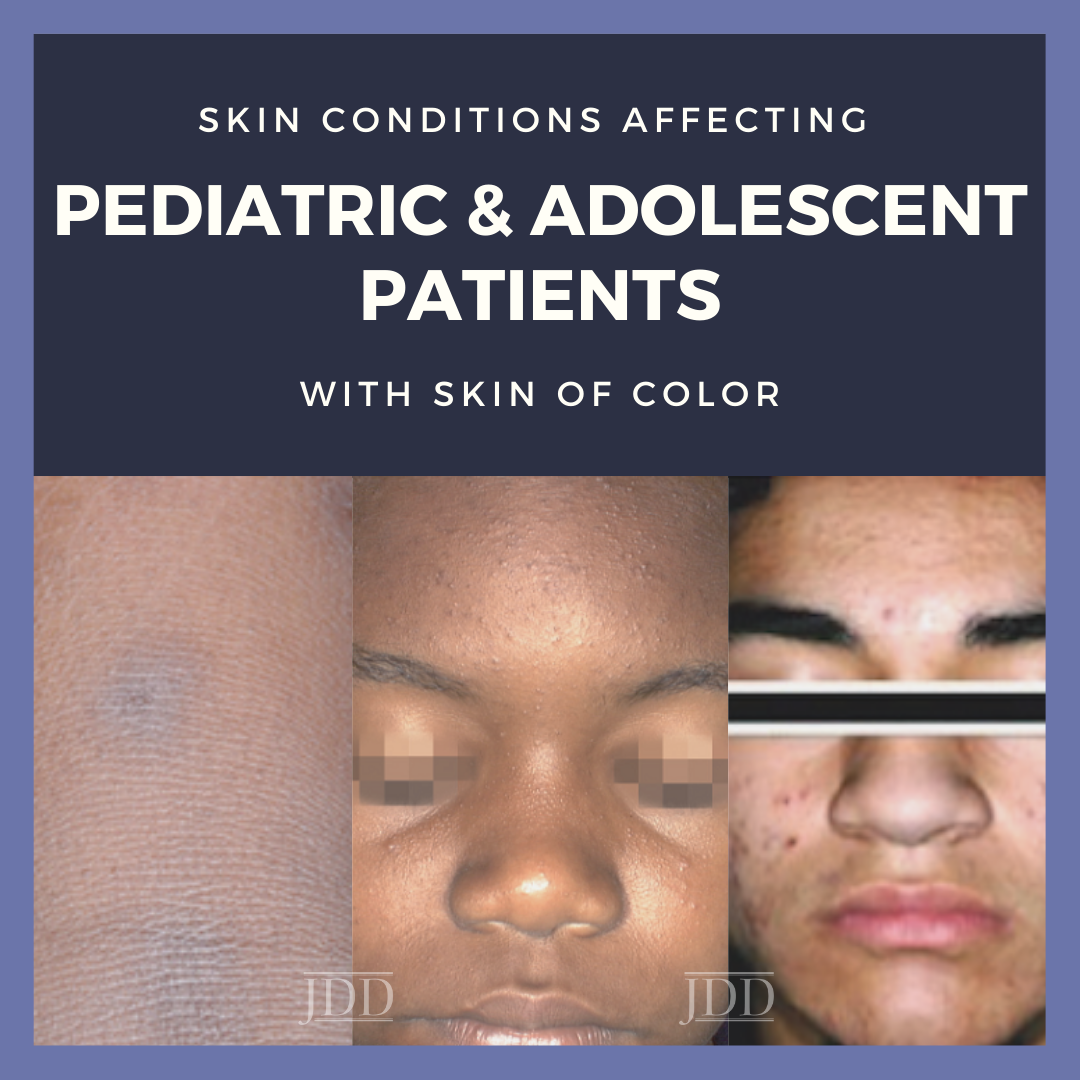

Sprinkled with many clinical pearls, Dr. Candrice Heath gave us an informative, case-based lecture at the 2021 Skin of Color Update: “Skin Conditions Disproportionately Affecting Pediatric & Adolescent Patients with Skin of Color.” Dr. Heath is an Assistant Professor and Director of Pediatric Dermatology at Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University and is active on social media @DrCandriceHeath. In this lecture, we will hear about a range of diseases that you will see in clinic along with recommended treatment approaches from a triple board-certified pediatric dermatologist!

Case 1:

A 2-year-old presents with an extremely itchy rash on his hands. No one else at home is itching. On exam, you see tense vesicles and pustules on the bilateral hands and feet.

Your first thought with this case is likely, “is this scabies?” Given the pruritic nature, Dr. Heath agrees that it would be reasonable to treat the entire household for possible scabies. However, the patient returns 2 months later with persistent disease, so now you need to do more thinking. Which leads you to the correct diagnosis of acropustulosis of infancy!1 This disease is more common in black males, from infancy to 2 years old. Patients present with intensely pruritic, 1-2 millimeter vesicles and pustules on their palms and soles. There is no clear etiology of this disease; some believe it may be a hypersensitivity reaction to a prior scabies infection, while others feel it may arise de novo. Treatment is high potency topical corticosteroids, which may make you nervous in an infant. But patients are often miserable from the pruritic nature, so strong topical steroids are necessary. Despite treatment, this disease can recur with long remissions in between. It will remit permanently after 2-3 years.2

Case 2:

7-year-old with a history of eczema in the antecubital fossa on hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment presents with itching “aaaaalllll over” (spelling is purposeful given this is the intonation Dr. Heath typically hears)! On exam, the patient has hyperpigmented linear patches on the upper back with many monomorphic, perifollicular papules.

This patient has a variant of atopic dermatitis, called follicular eczema. The small papules can be missed if you do not look closely or touch the skin using the “close your eyes” technique, as Dr. Heath calls it.3 You may see some erythema given the skin has recently been scratched. But in skin of color, erythema may be absent or more violaceous. This variant of eczema occurs more commonly in non-Hispanic black and Hispanic children, two populations that have greater odds of persistent atopic dermatitis compared to non-Hispanic white children.4,5 This disease is also more treatment-resistant in patients with skin of color.4,5

Treatments for follicular eczema include classic therapies – moisturizers and mid-potency topical corticosteroids utilizing the soak and smear method.6 Dr. Heath also encourages the use high potency steroids when appropriate for limited areas, like the feet or elbows, and in controlled quantity. One way to control quantity is to limit the size of the steroid you prescribe and number of refills. Other therapies include phototherapy (if the child can tolerate standing) and systemic options like Dupilumab, which is approved starting at 6 years old.6

Another important issue Dr. Heath discussed is the social and economic risk factors for atopic dermatitis. A study by Tackett et al showed that African American children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis are more likely to be exposed to lower household income, smoking, lower parental education level, lack of home ownership, and need to live between two addresses.7 It is imperative to understand these associations so we can recognize and address them in clinic. One way Dr. Heath does this is by asking, “who is participating in the child’s skin care?” Ensure that these individuals are at the visit or that pictures of the instructions are sent to the missing caretakers during the visit. If two households are involved, inquire if the family needs more than one tube of medication. It can also be helpful to provide doctor’s notes for school or daycare if moisturizer application is needed during the day.

Case 3:

4-year-old with a history of atopic dermatitis presents with complaints of fever, tiredness, and painful lesions on the face and neck. The patient’s immunizations are up-to-date. On exam, there are many monomorphic, erythematous to violaceous papules, vesicles, and pustules along with erosions with hemorrhagic crust on the face and neck.

Our third patient has eczema herpeticum, a disease that often occurs in younger patients (aged 3-4 years old) and non-white children, more commonly in Asian patients compared to black and Native American patients.8 Interestingly, eczema herpeticum is less likely to occur in lower income households.8 Treatment is with intravenous acyclovir. Complications of this disease include viremia, keratoconjunctivitis, and secondary bacterial infections.

Case 4:

15-year-old teenager presents with subtle hypopigmented macules on the middle of her forehead for several months.

The patient only brings up these white spots on her forehead. But you are also curious about her scalp, since she reports itching and flaking of the scalp, as well. You correctly diagnose the patient with seborrheic dermatitis. While this disease does not occur in children, it often starts in the teenage years after puberty.

Case 5:

15-year-old with a history of atopic dermatitis presents with worsening dark marks on the face.

Based on the patient’s exam with erythematous papules, pustules, and comedones, you diagnose him with acne complicated by post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. You know exactly what to do for acne and start the patient on benzoyl peroxide wash followed by topical clindamycin lotion in the morning and tretinoin cream after washing with a gentle cleanser at night. However, in the parking lot, the patient says that the visit was a waste of time because, “all I wanted was something for the dark spots.” This disconnect is common between doctors and patients with skin of color. Even though you are targeting the dark spots with your treatment regimen, you must acknowledge that you see the pigment change and affirm that the treatment plan is going to help the underlying cause of this change.3

Dr. Heath made one final point about acne – in teens with severe acne with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring, consider aggressive treatment with Isotretinoin.9,10 Long-term scarring significantly impacts patients’ quality of life and recent data shows that Isotretinoin is used less frequently in skin of color.

With these five great cases in mind, I hope you all feel better-prepared to diagnose and treat pediatric patients with skin of color. We learned about diseases that are more common in patients with skin of color, including acropustulosis of infancy, papular eczema, and eczema herpeticum. We also heard about pigmentary changes that can occur with both seborrheic dermatitis and acne. When patients present for these pigmentary alterations, do not allow a disconnect to occur with your patients. Make sure patients are aware of the cause of the pigment changes and how you are treating it!

References

-

- Mancini AJ, Frieden IJ, Paller AS. Infantile acropustulosis revisited: history of scabies and response to topical corticosteroids. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15(5):337-341. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015337.x

- Silverberg NB. Infantile Acropustulosis. In: Pediatric Skin of Color. Springer; 2015:323-325.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color. Pediatr Dermatol. Published online March 2, 2021. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups-Variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(4):340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Kim Y, Blomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Incidence and Persistence of Childhood Atopic Dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(4):827-834. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.029

- Silverberg NB, Durán-McKinster C. Special Considerations for Therapy of Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatologic clinics. 2017;35(3). doi:10.1016/j.det.2017.02.008

- Tackett KJ, Jenkins F, Morrell DS, McShane DB, Burkhart CN. Structural racism and its influence on the severity of atopic dermatitis in African American children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(1):142-146. doi:10.1111/pde.14058

- Hsu DY, Shinkai K, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of Eczema Herpeticum in Hospitalized U.S. Children: Analysis of a Nationwide Cohort. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(2):265-272. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.039

- Heath CR. Managing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2019;103(2):71-73.

- Alexis AF, Harper JC, Stein Gold LF, Tan JKL. Treating Acne in Patients With Skin of Color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(3S):S71-S73. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.027

This information was presented by Dr. Candrice Heath at the 2021 Skin of Color Update virtual conference held on September 10-12, 2021. The above highlights from her lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Emily Murphy.

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on Skin of Color Dermatology here.