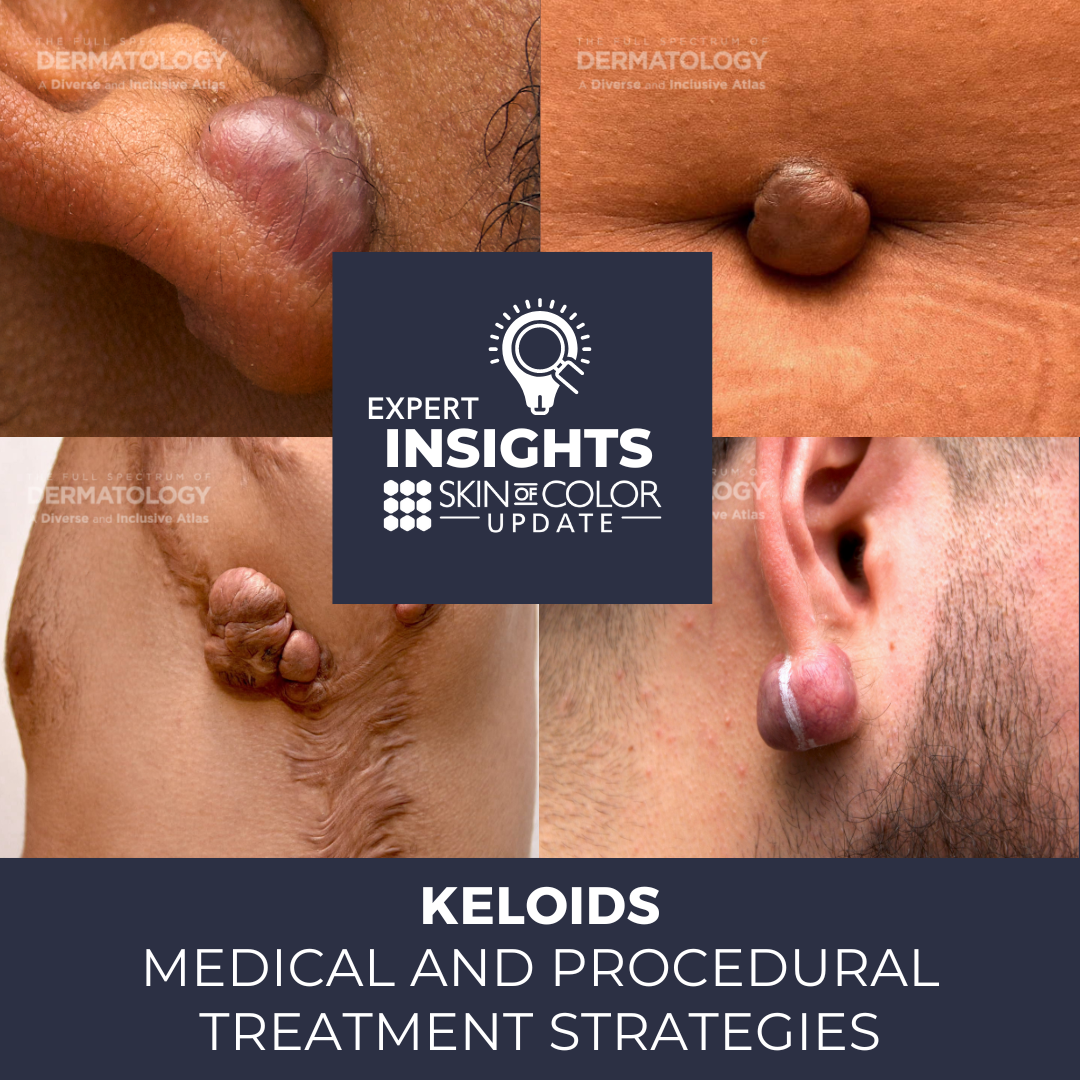

Patients with skin of color are at significantly higher risk of developing keloid scars compared with their fair-skinned counterparts. At the 2022 Skin of Color Update, Dr. Eva Kerby, Assistant Dermatology Professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, and Dr. Maritza Perez, Professor of Dermatology at the University of Connecticut, shared their pathogenesis-informed medical and procedural treatment strategies for managing keloids of all shapes and sizes.

Three Basic Principles of Keloid Management

Principle 1—Treat the Patient, Not Just the Scar

Keloids cause both symptomatic and aesthetic suffering. Therefore, Dr. Kerby recommended treating the patient, not just the scar. Open communication fosters a strong physician-patient relationship. Explain the molecular pathophysiology of keloid formation in terms the patient can understand. A knowledgeable patient will have more realistic expectations of their treatment plan and be mentally prepared for high recurrence rates and for limitations on how much the appearance of the keloid can be improved. It is important to set an optimistic tone while counseling the patient, however, as treatment can still achieve significant reduction in pain and pruritus. Furthermore, counsel the patient on preventable risk factors for new keloid development including elective cosmetic surgeries, piercings, etc. Aggressively control acne, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and any other chronic causes of skin injury.

Principle 2—Let Keloid Morphology Guide Your Treatment Plan

To begin, it is important to differentiate keloids from hypertrophic scars. Hypertrophic scars can be treated with topical or external therapies such as silicone sheets/gel, fluradrenolide tape, and pressure therapy. Keloids, which extend beyond the borders of the scar, do not respond as well to these therapies. One exception is following post-operative excision. Morphology of the keloid determines optimal treatment approach.

Thick and mildly elevated keloid scars are called sessile keloids. These scars can be treated with intralesional Kenalog. Select the smallest gauge needle that overcomes resistance while minimizing trauma, use with a 1 cc Luer lock syringe, and consider retrograde injection technique. Two cycles of spray cryotherapy can be administered prior to injection. For pain control, Dr. Kerby prefers compounded topical lidocaine 23% with 7% tetracaine under occlusion. Other approaches include anesthesizing with intralesional lidocaine prior to steroid injection, or mixing lidocaine with steroid. Dr. Kerby recommends a limit of 40-80 mg of steroid per session and adjusts the concentration of steroid to the thickness of the keloid (10 mg/mL for thinner areas, 20 mg/mL for thicker areas). Injections are generally spaced every four weeks.

Dramatically elevated nodular keloids can be challenging to treat. Dr. Kerby recommends contact cryotherapy to debulk nodular keloids prior to other treatments for its affordability and efficiency. She advises selecting patients for this carefully, as pain, swelling, blistering and dyspigmentation are possible. After numbing the keloid with lidocaine, roll a 4×4 woven gauze into a 6 or 8 cc test tube depending on the keloid size, dip it into a Styrofoam cup filled with liquid nitrogen, and touch the tube to the keloid. Avoid dripping liquid nitrogen on the skin, as that can cause cold-induced necrosis. Start with one freeze-thaw cycle, up to two in subsequent sessions. Check on the patient in four weeks, and counsel about potential dyspigmentation, which will likely resolve with time.

Other treatments for nodular keloids include intralesional Botox, which prevents muscle and skin contraction near keloid tissue. This reduces scar tension and decreases fibroblast proliferation. However, as 70-140 units per treatment are needed monthly, this is a costly option. A six-month course of oral pentoxifylline 400 mg TID in addition to intralesional steroids was shown to decrease postoperative keloid recurrence rates compared with intralesional steroids alone. Oral pentoxifylline inhibits fibroblast proliferation, which helps reduce pain and pruritus in existing keloids. There are also case reports of dupilumab decreasing pain after 4 weeks and reducing keloid size after 7 months. Notably, the pain recurred after dupilumab was discontinued.

Have a toolbox for treatment-resistant keloids

Butterfly-shaped sternal keloids can be especially difficult to treat. Dr. Kerby usually starts with a 1:1 mixture of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and intralesional Kenalog, as patients with skin of color can develop pain, hyperpigmentation, and ulceration with higher concentration of 5-FU. Managing patient expectations is important, as it takes time to appreciate clinical improvement. 5-FU is not recommended during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Clinical Pearl: Utilize a combination of medical and laser treatments for treatment-resistant keloids when possible.

Keloid Pathogenesis

The normal wound healing process is a delicate balance of proliferative and apoptotic responses. In keloid pathogenesis, there is an increased proliferative response, as well as increased resistance to apoptosis. Overall, the molecular milieu favors induction of fibrosis. In particular, pro-fibrotic Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-8, and IL-13 dominate, while anti-fibrotic cytokines such as IL-12 and IFN-gamma are absent. Other pro-fibrotic factors that are upregulated include TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, while antifibrotic TGFβ3 is downregulated. This activates pro-fibrotic downstream signals such as SMAD3, fibronectin, COX-1, COX-2, and integrin α2β1, and matrix metalloprotease 13. Decreased p53 and increased Bcl2 also increase resistance to apoptosis.

Keloid molecular pathophysiology offers numerous non-interventional therapeutic opportunities. With regards to topical therapies, flavonoids can be used to inhibit SMAD 2, 3, and 4. Imiquimod increases IFN-gamma and promotes apoptosis. Possible intralesional therapies include recombinant TGFβ3 and antibodies against TGFβ1 and TGFβ2. Corticosteroids decrease inflammation and collagen production, while bleomycin reduces TGFβ1 and increases apoptosis. 5-fluorouracil decreases fibroblasts, increases apoptosis, and decreases TGFβ1. Botox decreases TGFβ1, and dupilumab inhibits IL4 and 13.

With regards to interventional therapies, keloids can be treated with cryotherapy, laser (carbon dioxide ablative with steroids, non-ablative Nd:Yag, and PDL), re-excision and/or radiation with intralesional steroids or chemotherapy, radiation, autologous fat grafting, stem cell injections, and combination treatments. Future anti-fibrotic therapies in the pipeline include imatinib mesylate, tacrolimus, IL-10, stem cell therapies, genetic, and epigenetic therapies.

A variety of medical and procedural tools are available for keloid treatments, and more are on the horizon. Optimal treatment is determined by the morphology of the keloid. Remember to treat both the patient and the scar.

This information was presented by Drs. Eva Kerby and Maritza Perez at the Skin of Color Update Conference held September 9-11, 2022. The above highlights from their lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Joyce Cheng.

Did you enjoy this article? You can find more here.