At the 2023 Skin of Color Update Conference, attendees had the exciting opportunity to listen to Dr. George Han, MD, PhD, from Northwell Health in New York, discuss the prevalence and characteristics of certain skin conditions, primarily in Asian populations. His lecture highlighted the differences in the presentation, genetics, and treatment responses among Asians compared to other ethnic groups for inflammatory skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, acne vulgaris, and rosacea. He emphasized the importance of considering cultural factors, varying diagnostic criteria, and the influence of genetics and environmental factors when addressing these skin conditions in Asian patients. Below you can read about key points highlighted by Dr. Han categorized by disease.

Atopic Dermatitis (AD):

-

- High prevalence among Asian populations

- In children, prevalence is highest in African Americans (20.2%), Asians (13%), and Whites (12.1%)

- In Adults, prevalence is highest in Whites (10.5%), Asians (9.1%), and African Americans (7.7%)

- Differences within Asia

- A 2012 study in Shanghai, China, surveyed 10,000 children and found a prevalence of 8.3%. Highest prevalence was in the core urban area (10.2%) and lowest was in the most rural area of Shanghai (4.6%): a 2-fold difference!1

- South Asians (i.e., from India) have less AD than East Asians, however data is very poor or lacking in India.2

- In Japan, the demographics of patients have shifted to having more adult AD.

- In 1967, 75% of presenting patients were within the age group of 0-9 years. In contrast, in 1996, the peak age of presentation was for the age group of 20-29 years.3

- AD tends to be more severe in older age groups.

- Differences in presentation

- Asian patients with AD have a higher likelihood of presenting well-demarcated and lichenified plaque-like skin lesions.4

- Histologic differences between Asian and European AD4

- Asians have increased epidermal thickness (comparable to psoriatic lesions) and Ki67 (index of proliferation)

- Asians have more frequent parakeratosis and focal hypogranulosis and have more elongated rete ridges.

- Treatment considerations in Asian patient populations

- Steroid phobia is common in Asia.3

- Preference for non-steroidal medicines

- In Japan, they have regimens with down-titrated use of the non-steroidal medications, almost as a preventative measure. For example, a standard regimen for tacrolimus following an AD flare is to apply the medication three times weekly, then twice weekly, then once weekly. They found a reduction of flare intensity and prolonging of time between flares by adopting this regimen.

- Antihistamines are often used as a first-line treatment in some Asian countries.

- What about Traditional Chinese Medicine?

- Traditional medicine may be the first option patients resort to, and there IS in fact some evidence in support of this to treat AD

- A systematic review of eight high quality randomized clinical trials showed that Chinese herbal medicine improved AD severity and sleep quality of patients with AD. Notable to mention that there was no effect on quality of life or IgE levels.5

- A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial found that acupuncture reduced itch and wheal size compared to “placebo acupuncture” or no acupuncture only when performed after a skin prick test challenge with dust mite or grass pollen. 6

- Traditional medicine may be the first option patients resort to, and there IS in fact some evidence in support of this to treat AD

- High prevalence among Asian populations

Psoriasis:

-

- Lower prevalence in Asian countries (~0.14- 0.5%) compared to the US

- Interestingly, the prevalence in Asians in the US is 2.5% comparable to the prevalence in white individuals (3.5%) and higher than in Hispanic or Black individuals.

- Why? Dr. Han proposes it could be an interplay between genetics and environment or differences in the diagnostic criteria.

- Interestingly, the prevalence in Asians in the US is 2.5% comparable to the prevalence in white individuals (3.5%) and higher than in Hispanic or Black individuals.

- Higher rates of psoriasis susceptibility genes in Caucasian patients than in Chinese patients as evidenced by a genome-wide metanalysis.7

- Increased prevalence of generalized pustular psoriasis in Asian populations .8

- Large plaque psoriasis tends to be Western-specific.

- Small plaque psoriasis tends to be specific to Asians (also more persistent)

- Asians tend to have more severe psoriasis at presentation and are more likely to be erythrodermic (or pustular, as noted in prior point).

- Asians are less likely to have inverse psoriasis.

- No treatment differences identified in Asians vs Caucasians with adjusted analysis.9

- Lower prevalence in Asian countries (~0.14- 0.5%) compared to the US

Vitiligo:

-

- Prevalence estimated to be lower than in Caucasians.10

- A population-based cohort study from China found overall prevalence to be 0.56%

- In Caucasians, prevalence is ~1%

- Global prevalence is 0.1%- 2%

- Important to recognize significant stigmatization in South Asians as vitiligo as historically been tied to leprosy leading to social ostracization.

- Prevalence estimated to be lower than in Caucasians.10

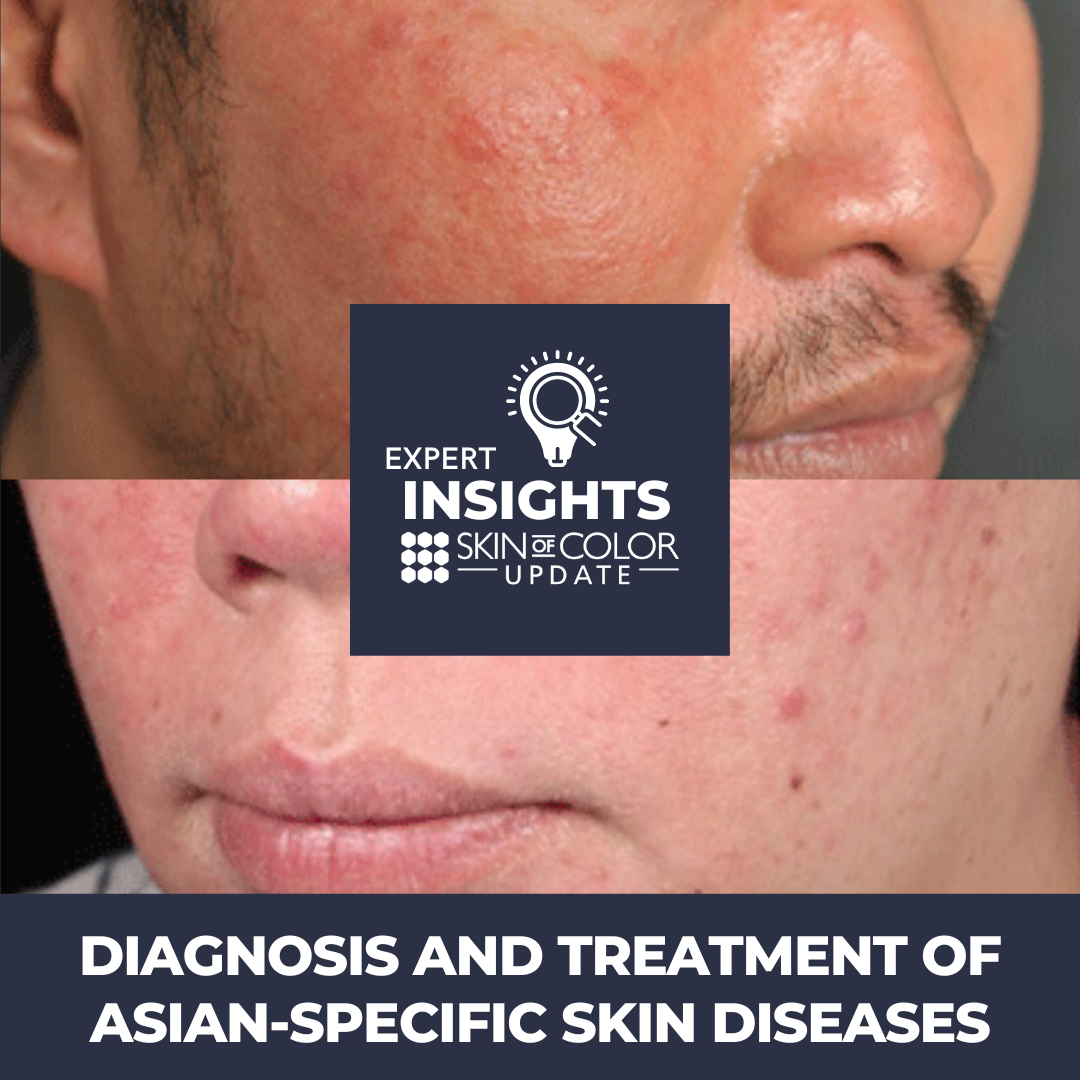

Acne Vulgaris:

-

- Known as a disease of Western civilization, but it is also highly prevalent in Asian populations.11

- In the US, acne is the most common reason bringing Asian patients to a dermatologist.

- Phenotype of acne in Asians is different than Caucasians.12

- Inflammatory acne is twice as common as comedonal acne in Asians. On the contrary, comedonal acne is 1.5x more common than inflammatory acne in Caucasians.

- Phenotypic differences affect treatment approach to acne.

- Isotretinoin should be started at a lower dose with a longer tapering period.

- Asian isotretinoin guidelines start with 0.25-0.5mg/kg. Once the acne has cleared, they taper for 2 months afterwards.

- Once patient’s acne is cleared, isotretinoin is usually tapered for 2 months afterwards.

- Consider long-term anti-inflammatory treatments such as sarecycline

- Known as a disease of Western civilization, but it is also highly prevalent in Asian populations.11

Rosacea:

-

- Associated with sensitive skin, which is common in Asian patients.

- Asians may be more open to receiving recommendations for over-the-counter products.

- Relatively high proportions of ocular rosacea in Asian populations (almost 15%!)13

- Botulinum toxin injection as a potential treatment for erythema in rosacea

- It is mentioned in the US guidelines, but it is a formal recommendation in the Chinese guidelines.14

In conclusion, the complex interplay of historical, genetic, and cultural factors underscores the nuances inherent in the diagnosis and treatment of skin diseases within Asian populations. Dr. Han highlights many unique features that can help dermatologists tailor treatment approaches while better recognizing the daily impact of skin diseases in Asian patient populations. This presentation also revealed the need for more research and guidelines specific to Asian populations to optimize patient care.

References:

-

- Xu, F., Yan, S., Li, F., Cai, M., Chai, W., Wu, M., Fu, C., Zhao, Z., Kan, H., Kang, K., & Xu, J. (2012). Prevalence of childhood atopic dermatitis: an urban and rural community-based study in Shanghai, China. PloS one, 7(5), e36174. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036174

- , Goh, C. L., & Giam, Y. C. (2002). The prevalence and descriptive epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in Singapore school children. The British journal of dermatology, 146(1), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04566.x

- Furue, M., Chiba, T., & Takeuchi, S. (2011). Current status of atopic dermatitis in Japan. Asia Pacific allergy, 1(2), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.5415/apallergy.2011.1.2.64

- Noda, S., Suárez-Fariñas, M., Ungar, B., Kim, S. J., de Guzman Strong, C., Xu, H., Peng, X., Estrada, Y. D., Nakajima, S., Honda, T., Shin, J. U., Lee, H., Krueger, J. G., Lee, K. H., Kabashima, K., & Guttman-Yassky, E. (2015). The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 136(5), 1254–1264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.015

- Cai, X., Sun, X., Liu, L., Zhou, Y., Hong, S., Wang, J., Chen, J., Zhang, M., Wang, C., Lin, N., Li, S., Xu, R., & Li, X. (2022). Efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal medicine for atopic dermatitis: Evidence from eight high-quality randomized placebo-controlled trials. Frontiers in pharmacology, 13, 927304. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.927304

- Pfab, F., Huss-Marp, J., Gatti, A., Fuqin, J., Athanasiadis, G. I., Irnich, D., Raap, U., Schober, W., Behrendt, H., Ring, J., & Darsow, U. (2010). Influence of acupuncture on type I hypersensitivity itch and the wheal and flare response in adults with atopic eczema – a blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Allergy, 65(7), 903–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02284.x

- Yin, X., Low, H. Q., Wang, L., Li, Y., Ellinghaus, E., Han, J., Estivill, X., Sun, L., Zuo, X., Shen, C., Zhu, C., Zhang, A., Sanchez, F., Padyukov, L., Catanese, J. J., Krueger, G. G., Duffin, K. C., Mucha, S., Weichenthal, M., Weidinger, S., … Liu, J. (2015). Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies multiple novel associations and ethnic heterogeneity of psoriasis susceptibility. Nature communications, 6, 6916. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7916

- Kim, J., Oh, C. H., Jeon, J., Baek, Y., Ahn, J., Kim, D. J., Lee, H. S., Correa da Rosa, J., Suárez-Fariñas, M., Lowes, M. A., & Krueger, J. G. (2016). Molecular Phenotyping Small (Asian) versus Large (Western) Plaque Psoriasis Shows Common Activation of IL-17 Pathway Genes but Different Regulatory Gene Sets. The Journal of investigative dermatology, 136(1), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1038/JID.2015.378

- Zhang, D., Qiu, J., Liao, X., Xiao, Y., Shen, M., Deng, Y., & Jing, D. (2022). Comparison of Efficacy of Anti-interleukin-17 in the Treatment of Psoriasis Between Caucasians and Asians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in medicine, 8, 814938. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.814938

- Dahir AM, Thomsen SF. Comorbidities in vitiligo: comprehensive review. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(10):1157–1164. doi:10.1111/ijd.14055

- Cordain, L., Lindeberg, S., Hurtado, M., Hill, K., Eaton, S. B., & Brand-Miller, J. (2002). Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Archives of dermatology, 138(12), 1584–1590. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.138.12.1584

- Perkins, A. C., Cheng, C. E., Hillebrand, G. G., Miyamoto, K., & Kimball, A. B. (2011). Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV, 25(9), 1054–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03919.x

- Bae, Y. I., Yun, S. J., Lee, J. B., Kim, S. J., Won, Y. H., & Lee, S. C. (2009). Clinical evaluation of 168 korean patients with rosacea: the sun exposure correlates with the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. Annals of dermatology, 21(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.243

- Rosacea Research Center, Chinese Society of Dermatology, Rosacea Professional Committee, Chinese Dermatologist Association, Gu, H., Hao, F., He, W., Jian, D., & Jia, Z. (2021). Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Rosacea in China (2021 Edition).

This information was presented by Dr. George Han during the 2023 Skin of Color Update conference. The above highlights from his lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Sarah Millan.

Did you enjoy this article? You can find more on Medical Dermatology here.